This month NASA is scheduled to launch the James Webb Space Telescope, far and away the largest, most complex and powerful space telescope ever built. With a primary mirror measuring more than 21 feet across and boasting a light collecting area nearly 60 times greater than that of the Hubble Space Telescope, the Webb telescope will be expand human vision to the furthest reaches of the known universe, some 13.5 billion light years away, a time when the first stars and galaxies were formed. This incredible instrument is the product of an international collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency, involving thousands of scientists and engineers whose collective ingenuity shows what human minds can achieve if tasked with something other than posting a comment on social media.

Unlike the Hubble telescope, which orbits Earth, the Webb telescope will take up an orbit around the Sun some one million miles away at the second Lagrange Point that will keep it in line with Earth 24/7. The Webb’s giant primary mirror is a multi-segmented complex of 18 gold-plated hexagons, protected by a five-layer thick sunshield the size of a professional tennis court. Also unlike the Hubble, which was optimized for collecting visible and ultraviolet light, Webb is optimized for collecting infrared light, which enables it to study stars whose light has “redshifted” in wavelength while traveling across vast distances to reach Earth. The Webb will be especially adept at identifying exoplanets – planets outside the Solar System – and analyzing their atmospheres. This should be an enormous boost to answering one of the most persistent and vexing questions in all of science: Are we alone? Is Earth the only home for life in the vast expanse of star-spangled black we call the universe?

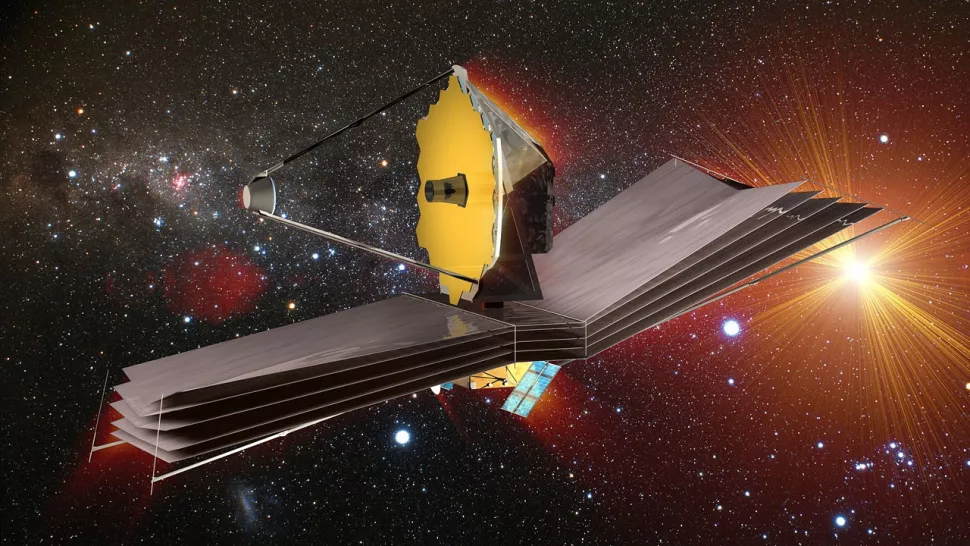

Artist’s illustration of the James Webb Space Telescope with its massive sunshield fully deployed. (Image credit: Northrop Grumman)

If you’re an odds-maker in Las Vegas and you’re taking bets that Earth is it as far as life goes, consider the following. Our own Milky Way galaxy harbors some 100 billion stars with an estimated 10 trillion planets orbiting those stars. The Milky Way is but one of some 200 billion galaxies we’ve observed – and not a particularly large galaxy either. This means there could be thousands upon thousands of times more planets in the universe than all the grains of sand on all the deserts and beaches on Earth. If it is truly the case that our “pale blue dot” is the only home for life in the universe, there is only one word to describe the odds: “Miraculous!”

Since scientists aren’t given to accept miracles without empirical evidence, they’ve been searching for signs of life on other worlds since the invention of the telescope and the realization that Earth is but one planet in a system of planets orbiting our Sun. This search has long excited the general public as well as the scientific community, though the search has also sometimes engendered caution and even fear. For example, in 1877, astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, using a telescope to study Mars, observed features on the surface he called “canali,” the Italian word for “channels.” The English press mistranslated the word into “canals,” which gave rise to the idea that Mars was home to an intelligent civilization. Popular speculation about the canals of Mars and the Martians who built these canals led to the publication in 1898 of H. G Wells’ The War of the Worlds, a novel about a Martian invasion of Earth. This novel would go on to be the inspiration for an infamous radio broadcast by Orson Welles in 1938 that sparked panic in the streets.

We now know that Mars is home to neither canals nor LGM, the “Little Green Men” acronym that astronomers somewhat mockingly attached to the SETI effort – the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. The term “little green men” may have come from the John Carter on Mars series of novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs, which began around 1912, though the Tharks – the green men in those books – weren’t little.

The LGM moniker reflects how non-seriously the serious scientific community took the SETI effort until a conference in 1961 organized by radio-astronomer Frank Drake and held at the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia. Among those attending the three day affair was a post-doc student named Carl Sagan. At the conference, Drake unveiled an equation for estimating the number of planets that could potentially host intelligent life in the Milky Way galaxy. The Drake equation initially calculated that the Milky Way could host as many as 100,000,000 civilized planets. These were planets that would be similar to Earth in size, composition and atmosphere, with plenty of liquid water and orbiting a yellow sun in the so-called “Goldilocks zone,” meaning the planets were not too hot and not too cold but just right for sustaining life as we know it.

Drake was focused on detecting radio transmissions from technologically advanced beings on planets similar to ours, but Sagan did not believe the search for extraterrestrial life should be constrained to hearing from LGM on replicas of Earth. As a professor at Cornell, he devised experiments to simulate a wide range of atmospheric and surface chemistry conditions that revealed numerous alternative pathways by which the complex organic molecules of life as we know it can form. With this experimental evidence, along with his telegenic charisma and gift for public outreach, Sagan helped launch the field of astrobiology, in which scientists from across multiple disciplines seek to identify “biosignatures” – chemical markers created by living organisms.

Up until the 1990s, the worlds we could explore for signs of life were limited to our Solar System neighbors. Then through a combination of telescopes, satellites and probes, we began finding exoplanets. As of today we’ve identified thousands of them, most of which orbit stars – mainly red dwarfs not yellow stars like the Sun – but some of which are rogue, meaning they just spin through the Milky Way like nomads on a perpetual road-trip. We only see artist conceptions of what exoplanets look like because most are discovered by indirect methods such as “transit,” in which a star’s light is observed to dim as a planet passes between it and the telescope; and “wobble,” in which the gravitational effects of a planet orbiting a star cause a detectable change in the star’s light spectrum. The few exoplanets that have been directly observed appear only as tiny dots of not-so-bright light.

In addition to expanding the number of worlds that might harbor life, we’ve also expanded the definition of “life as we know it.” During the past decades, scientists here on Earth have discovered colonies of microorganisms thriving in environments that would be considered too hot, too cold or too dark under the Drake equation: super-hot vents at the bottom of the ocean; super-cold lakes far beneath the Antarctic ice; hairline cracks in bedrock miles below our planet’s surface. These microbes, collectively classified as “extremophiles,” have adapted to levels of acidity, alkalinity, toxicity or radiation that would spell certain death for life as defined in the Drake equation.

So what are the biosignatures for which astrobiologists are searching these days? The most obvious target is oxygen. Life needs oxygen right? It powers the metabolic processes that sustain living cells and enable them to thrive and replicate. Then there’s carbon of course. Carbon atoms sprout four chemical bonds that readily link up with other atoms to form chains of complex molecules such as DNA and RNA. Also, carbon is one of the five most abundant elements in our galaxy along with hydrogen, helium, oxygen and nitrogen. Speaking of hydrogen and oxygen, scientific consensus holds that liquid water is essential to any form of life as it is a powerful solvent that can dissolve and transport nutrients throughout the body of an organism.

As logical as that all sounds, what it really means is we only know the biosignatures of life that is based on carbon; in other words, life as we know it. But there are other fluids that could serve the same nutrient dispersal purposes as water, and there are proposed scenarios under which sulfur could replace carbon as a biological building block. For this reason, some astrobiologists have suggested that in addition to biosignatures, we also look for evidence of motion with the idea that all living organism move in response to their environment. But supersensitive motion detectors created by LGM on a distant planet and aimed at Earth wouldn’t detect snottites.

First discovered in a cave in Mexico filled with poisonous hydrogen sulfide and carbon monoxide gases, and through which runs a creek of sulfuric acid water, snottites are chemotrophs that oxidize hydrogen sulfide as their metabolic energy source. During metabolism, they form films on cavern walls that look like the blobs of mucus you spray when you sneeze from a cold or flu. Snottites are among several different types of extremophiles called “bioverms” because their colonies form patterns of lines known as vermiculations. It is easy to imagine snottites and other bioverms or extremophiles living in Martian caverns, or beneath the global wide ice cap that is the Jupiter moon Europa, or even in the methane seas of the Saturn moon Titan, just waiting for us to discover them. (See my novel Chromeleon Part One: A Greater Good)

So what does it mean if and when we do discover life on another world? Pubic polls in this country consistently show a general feeling of “positivity,” as some would say. This reflects the enthusiasm with which the public reacted in 1967 when Jocelyn Bell, a 24-year-old Cambridge University student doing research for her PhD, detected radio signals emanating from deep space that pulsed on and off every 1.3 seconds. The signal continued to pulse for about an hour then stopped. Approximately 23 hours 56 minutes later – the time it takes for Earth to rotate on its axis – the 1.3 second pulses resumed and once again stopped after an hour. Given the possibility that the signal was being transmitted by an alien civilization, Bell and her supervising professor Antony Hewish initially and tongue-in-cheek dubbed their discovery “Little Green Men-1.”

After extensive follow-up studies, Bell and Hewish determined that the actual source of the signals was in many ways as strange as if it had been LGM. Bell and Hewish had discovered a neutron star, a star that is only a tiny fraction the size of the Sun but much more massive. As the name implies, neutron stars are comprised almost entirely of neutrons (the subatomic particles that along with protons are found in atomic nuclei) jam-packed into a ball so dense that a spoonful of neutron star material would weigh several hundred million tons. Neutron stars that spin so rapidly they cast out radio signals, such as the one discovered by Bell and Hewish, are called “pulsars.”

The discovery of pulsars generated heavy media coverage around the world. Even though the signals turned out to be a false-alarm with regards to alien civilizations, the public attention garnered by the discovery of pulsars indicates that humans are at least intrigued by the idea of making contact with alien civilizations. There are of course exceptions. Some have warned that courting the attention of an advanced alien civilization could be dangerous, either remembering War of the Worlds or perhaps remembering happened to Native Americans when their existence became known to Europeans.

Given current sociopolitical conditions in this country, I can easily guess what would happen if Little Green Men – or Little Green Them as in gender-neutral non-binary beings – filled the sky with their ships and began incinerating major population centers with their death rays. Republicans would call the attack “Fake news!” and either deny it or declare “It’s not our problem!” even as they were being vaporized. Democrats would either form a committee and dozens of subcommittees to debate what should be done, or defer any action until Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema made their intentions known. Both sides would blame the other.

The scenario of an alien invasion I believe is highly unlikely as any civilization sophisticated enough to monitor what we humans are doing to our planet would no doubt conclude there’s no intelligent life here. If and when we do discover evidence of life on another world, it will most likely be in the form of microbes or fossils of microbes. And that discovery will be profoundly significant – perhaps the most important discovery in history even if it has no effect on the price of gasoline. The importance of such a discovery was beautifully expressed in Richard Powers new novel Bewilderment. When the narrator, an astrobiologist named Theo Byrne, is asked why it matters whether life occurs only on Earth, he answers: “Once is an accident. Twice is inevitable.”

.